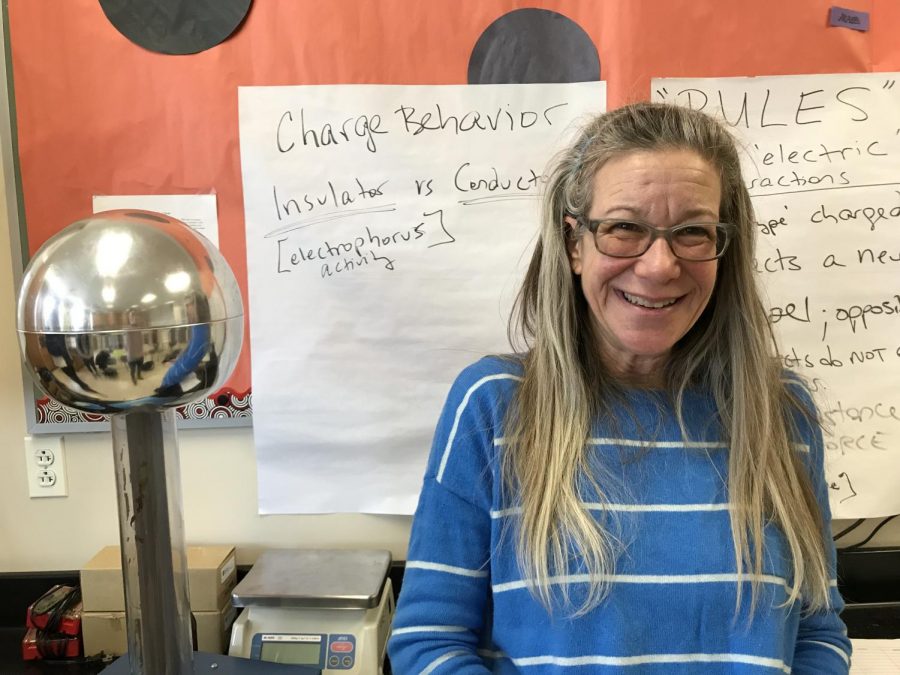

Inspiring Women in Science, One Student at a Time

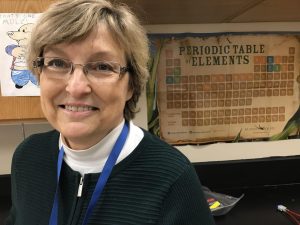

Elizabeth Petruska has been encouraging girls to go into physics in Hopkinton for 10 years.

Thirteen, this is the percentage of professional physicists that are women according to the American Institute of Physics.

It is because of this extremely low number that Elizabeth Petruska, a science teacher at Hopkinton High School, teaches physics to freshmen and seniors. She enjoys inspiring girls to go into the field.

Her passion for physics goes back to when she was a young girl. Petruska first became interested in this field in her own high school physics class, while she was doing math for why the spokes of a car’s wheel appear to be moving backward on the highway.

“That’s when I first fell in love with physics,” she said. Yet, she did not get much guidance. “My parents didn’t urge me to become a scientist. Nobody really said to me, ‘You should be a scientist!’”

In college, Petruska majored in English, but that high school physics class stayed with her.

“When I was thirty and I had gotten tired of waitressing, and working as a receptionist, and working as a secretary, and all this nonsense, I went ‘You know what, what do I really love?’ And I remembered that physics class in high school,” Petruska said.

“I kind of always knew, but it wasn’t until I was an adult where I had the guts to say ‘That’s really what I love. That’s what I’m going to do.’”

After emerging from lunch, DeMartino discusses how her interest in

science was spurred by Petruska’s class.

Sabine DeMartino, a freshman and former student in Petruska’s honors introduction to physics said, Petruska’s “passion for physics rubbed off on me, and the class became one of my favorites.”

Petruska has certainly made an impact at the Hopkinton High School.

Before taking Petruska’s class, DeMartino never considered a career in science or math. Petruska made her feel like she was qualified to go into these fields.

“She made me feel like I could do anything I put my mind to. And I am more compelled to try to take on a science-related career,” DeMartino said.

Petruska had a similar moment of clarity. While conducting research as a professor at a university, she became aware that inspiring a future generation of young women to pursue science was more important to her than research demanded in academia. She wanted to focus on teaching high school.

Soon the thing that pushed Petruska to teach was people’s reactions to her being good at math and physics. People would come up to her and say with a gasp, “You are so good at physics and math,” she said.

She was driven by the prospect of being able to change the message that society seemed to be sending women – it is unlikely for a girl to be good at math and science.

“Nobody was ever surprised that a boy was good at physics and math, but in my own life, people kept being surprised. And that felt really awful and kind of wrong.”

Other women must have experienced this feeling. As Petruska went through more levels of school, she found that fewer women continued with her. She believes that this is a societal norm and not because of women’s ability.

Petruska discusses the concept of electrostatics with three students

in her honors senior class.

AP Chemistry students and science fair participants benefit from Lechtanski’s experience in the field of science.

Petruska’s attitude towards girls seems to fit with the environment of the school according to Valerie Lechtanski, an Advanced Placement Chemistry teacher and head of the science department. Lechtanski is also a former mentor for the science fair at Hopkinton High School.

“I hope, that the females students here all know that we, the administration and the faculty, believe they’re capable of anything,” Lechtanski said.

“I think it’s really important for women to be involved in science and scientific research, whether its engineering or not, because I think women bring a whole different skill set and perspective to the same problem as a man might bring,” Lechtanski said.

The imbalance of power between men and women played a big role in Petruska’s decision to teach high school students.

“I want to see women run all the companies. And I want to see women run the government. And I want to see women making all of the scientific contributions in the centuries to come. Because you know what? The men have had a long time to do it. Now it’s our turn,” she said.