With censorship on the rise in recent years, the act of banning books has followed as an effort to shield readers from controversial yet imperative topics within literature.

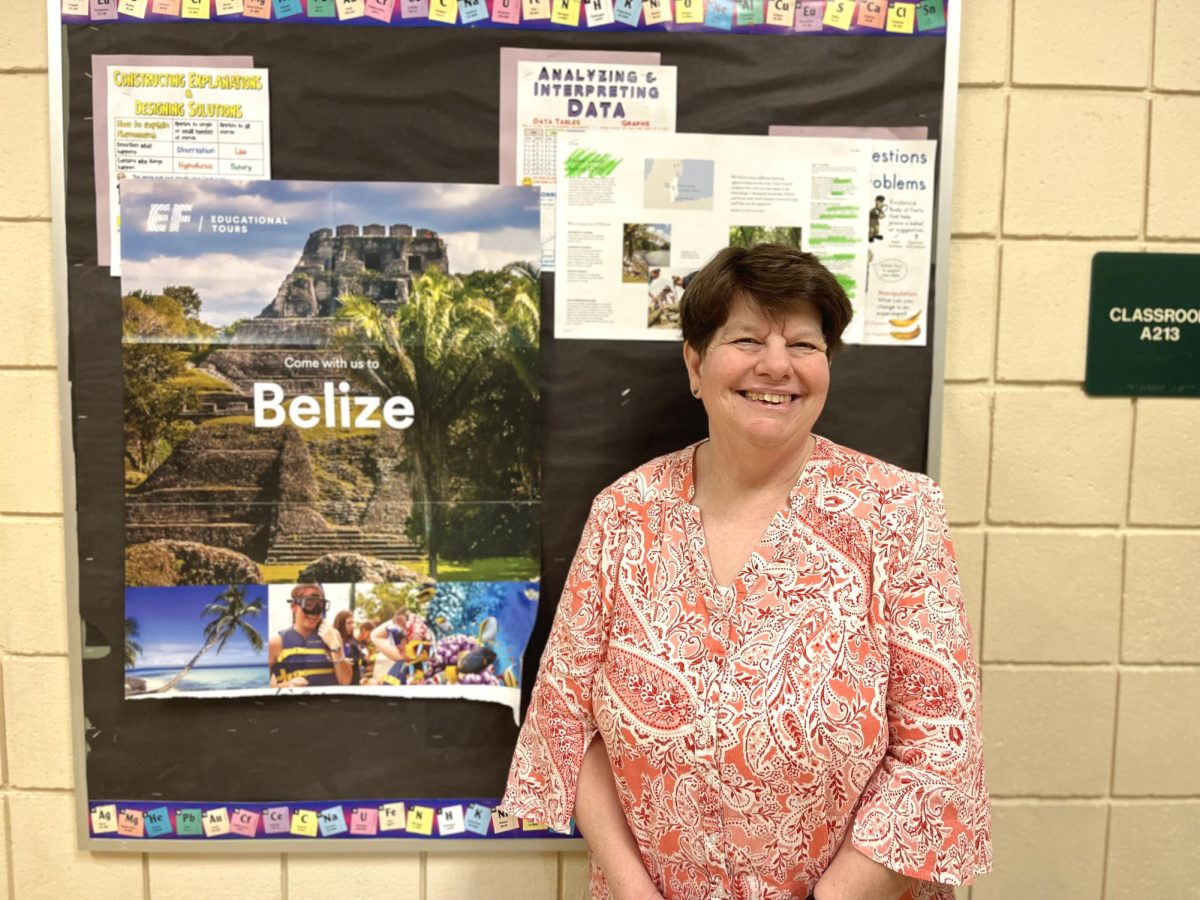

The banning of books has a long and complicated history, fueled by the desire to silence certain conversations in classroom settings. While some sympathize with the idea in hopes of dodging controversy, many push back against this idea: including Sophomore English teacher Benjamin Lally.

Lally, who has always been a strong advocate against book bans, walked through the process of getting a book banned.

“Most of the time, a book ban starts with complaints from parents in the community who object to some of the content that is in a book,” Lally explained. “What tends to happen is the complaint goes to the school board and the board decides whether the school has the right to be teaching that text or not. If you look over the list of what these books have in common that are being banned, it seems we are trying to restrict the variety of voices that schools teach.”

Lally has also noted in the past few years, efforts to ban books are often organized by politically motivated groups rather than genuinely concerned individuals with connections to specific school systems. This conflicts with Lally’s goal to educate students about a wide range of topics that welcome different perspectives.

“One of the things I try to get across in my classroom the most is freedom of thought, creative thinking, and processing things for yourself—not just taking in what people are handing to you. If we are saying as a school, district, or country that you are not allowed to talk about those things, it pulls the rug out from under me,” Lally said.

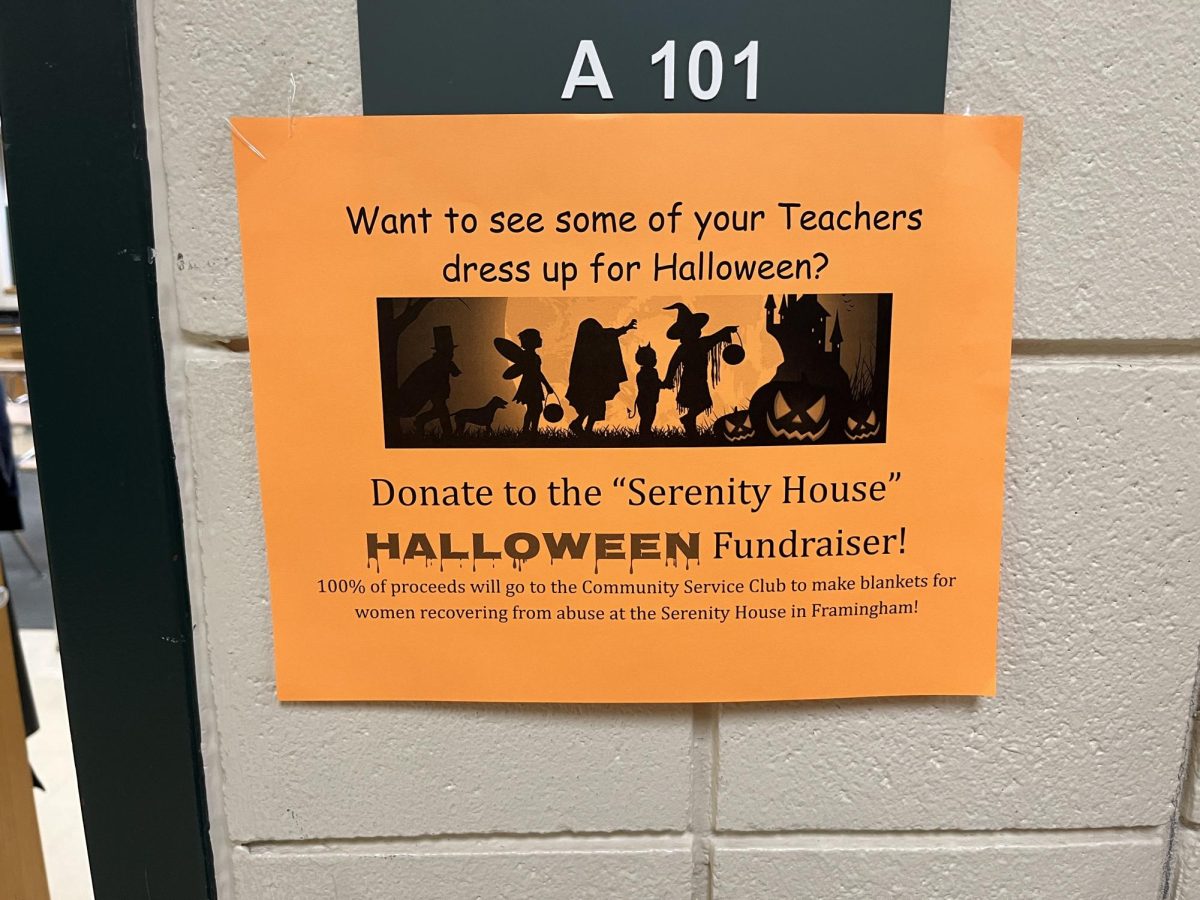

Student voices have also emerged against the censorship of literature.

Sophomore Tenley Winn dedicates a lot of her time to reading a variety of books, including books that are banned or frowned upon. As a high school student, such topics do not intimidate her but rather pique her interest even more.

“I think it is really important to continue and welcome the discussions that come along with reading banned books,” Winn said. “I have always looked forward to in-class lessons or Socratic seminars where we can talk about what we read and dive into the importance of a novel. I do not think banning books is very ethical or fair because it aims to censor critical thinking.”

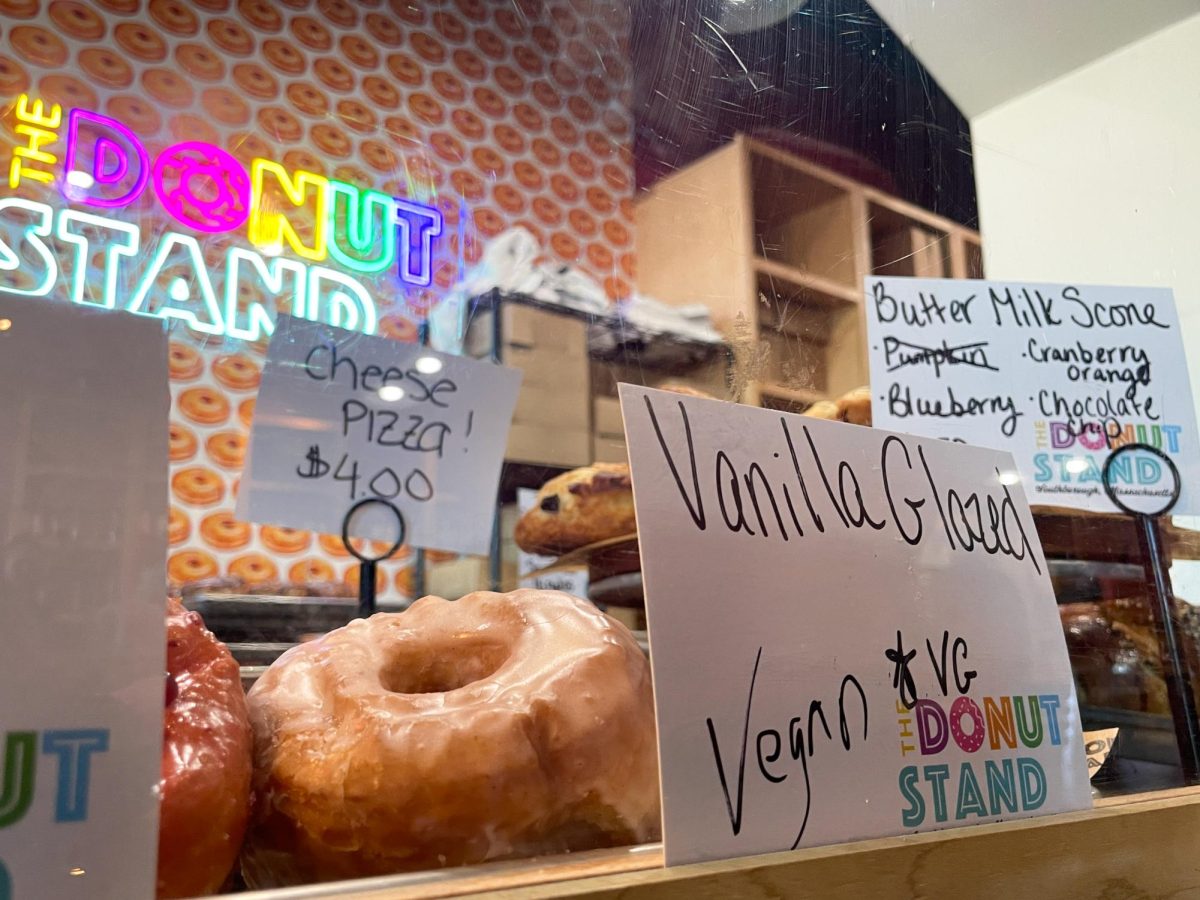

Beaufort County, South Carolina, has 97 challenged books within their school district. Hummingbird Books, a local bookstore in Chestnut Hill, Massachusetts, showed its support by participating in Banned Books Week from October 1-7.

The bookstore held a fundraiser and sent copies of banned books to Families Against Banned Books and Lowcountry Pride, two organizations that distribute challenged literature in hopes of combatting censorship by helping to provide banned books to affected communities.

“I think it’s important for Hummingbird Books to be part of the fight against banned books because we believe that no book should be banned and that all people and all children have the right to read,” explained Lily Spar, the lead book buyer for Hummingbird Books. “As members of the book world and with the privilege of being part of a community that uplifts a diversity of voices and books, we feel it is our duty to support those in areas that have particularly high levels of banned books.”

In most cases, the banning of a book has to do with content involving romantic relationships, religion, LGBTQIA+, gender identity, or race. Book banning has also provoked legal disputes in which the opposing party says it is an attack on the First Amendment and an attempt to restrict free speech.

Lila Davidson is an English major in her senior year at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. She took a semester-long class centered around banned books in which she read notoriously challenged titles and learned about why people think literature can be dangerous.

“My immediate reaction to book banning was that it is horrible and should not happen, especially as an English major who loves books and literature. The idea that we would restrict access to books is sad to me but in my class, we tried to empathize with the people who would be so scared of a book that they would try to get it banned so nobody could read it. We tried to understand what would make someone feel that way and compel somebody to spread that message,” Davidson said.

Davidson thanks her professor and class for opening her eyes to the realities of book banning. According to CNN, in the 2022-2023 school year alone, more than 3,300 books were banned.

“Something my professor said that stuck with me is ‘Never underestimate what will be taken from you as an adult in the name of protecting children.’,” Davidson continued. “In the world that we are in now, people might underestimate books or literature just because of technology, social media, and AI. Still, books have power to the point in which they garner fear in people about what their impact will be. The core of book banning is fear. There is a lot of fear of societal change.”

Davidson explained that just because a book is banned, that does not mean that it is banned everywhere. This is why certain school districts, including Hopkinton, can teach banned books while there could be another town in which the same book would not be allowed in the curriculum.

“Literature will always exist,” Davidson said. “I feel the conversation about banning books will as well, because books are always going to strike fear in people. I think this is a good thing.”